Evidence based dental trauma treatment

The Dental Trauma Guide

A source of evidence based treatment guidelines for dental trauma

INTRODUCTION

Dental traumatology, the evidence problem

Dental trauma cases often result in a treatment sequence that involves both general dentists and many specialists. Optimal treatment relies upon the expertise of a broad spectrum of dental specialists such as oral and maxillofacial surgeons, pediatric dentists, endodontists, orthodontists, prosthodontists and periodontists. The primary urgent care is frequently provided by the oral and maxillofacial surgeon or the pediatric dentist in a hospital emergency department setting. Subsequently the patient may be referred to a general dentist or an endodontist for secondary level care such as endodontic and restorative management. Alternatively, a general dentist is seeing the patient first and refers the patient to the specialists. Later the orthodontist and prosthodontists and periodontist may become involved with additional treatment. The long chain of referrals that are frequently seen in dental trauma cases means that control of the overall quality of treatment is often lost. The research activity in clinical traumatology has been extremely low and, in some sense, dental traumatology has become an orphan in dentistry. Dental traumatology relies on knowledge from research in many different specialties. For this reason, inter-disciplinary communication over the specialty borders is very important.

At the end of the last century there was a growing interest among all dental disciplines in analyzing the validity of existing treatment principles which lead to the recognition that evidence-based dentistry (EBD) with the randomized clinical trial (RCT) as the gold standard was the path for the future. In the famous pyramid “Mount evidence” most studies in dental traumatology belong at very low levels in the evidence pyramid. Only a couple of clinical RCTs have yet been published, and the prospect for future RCTs appears slim.

What is the cause of this problem?

First of all, the shared responsibility among several dental specialties makes research in dental traumatology complicated to organize and evaluate. Secondly, the ethical problems associated with getting informed consent from an injured child or adult to participate in an RCT are unavoidable. Reasonable arguments for carrying out the experiments despite these problems are rarely present. This obstacle is almost prohibitive for most RCTs dealing with treatment of acute traumatic dental injuries.

What are the alternatives?

Often animal models are the best alternative. They allow the researchers to control the parameters that may influence the outcome of the experiment in a fashion not attainable in human studies as the injuries can be inflicted by the examiner under controlled conditions. The current treatment guidelines give testimony to the value of animal experiments as they rely heavily on information obtained from animal studies.

Are animal experiments reliable?

This question has been examined carefully and monkey experiments seem to have a high degree of reliability, whereas the use of dogs often seem to give too optimistic results in relation to pulp healing. Rat studies appear to show a significant variance in periodontal ligament (PDL) healing with a likelihood of transient ankylosis, which makes this model unreliable in dental trauma studies affecting the PDL. For this reason, the principal findings from experimental studies should ideally be verified in clinical studies.

Are human clinical non-randomised studies a valid approach to assess the effect of dental trauma treatments?

If the correct statistical models are used, and groups with similar preinjury and injury characteristics can be isolated and compared, then it is possible to reduce the amount of interference caused by confounding factors. The results must however be evaluated with a certain amount of reservation as the risk of interference by confounding factors can never be eliminated with certainty. This type of analysis has so far offered useful information about the effect of various treatment procedures such as repositioning, type and length of splinting times and the use of antibiotics, RCT is not always possible to arrange in traumatology, especially not in the emergency situation. However, in later treatment situations when different drugs or treatments can be applied, randomization may be possible.

How big is the knowledge gap before we can have the necessary scientific foundation for offering evidence based treatment for all dental trauma types?

To answer that question one must start by focusing on the strongest predictor for successful/unsuccessful trauma healing, namely the trauma type. Dental trauma can be divided into 8 fracture and 6 luxation entities. Combination injuries in which both luxation and fracture have occurred are unfortunately frequent, causing 48 combinations which must be seen as 48 distinct healing scenarios. The complexity is further increased by the fact that trauma to the primary and the permanent teeth must be treated as separate entities. This results in 96 distinct trauma events! One single word may characterize treatment of traumatic dental injuries around the world: CHAOS.

Several predictors for pulp and periodontal healing have been identified for the individual trauma entities, some reflect the severity and nature of the trauma inflicted, some describe patient characteristics, and some reflect the influence of the choice of treatment. The strongest predictor appears to be the trauma type. The stage of root development appears to be a strong outcomes predictor for all types of dental trauma, and it affects both pulpal and periodontal healing. This is not surprising since a good blood supply is essential for pulpal healing and thus the size of the apical foramen is directly related to the revascularization potential of the affected tooth.

The choice of treatment offered has a direct effect on the healing outcome for luxation injuries where several treatment options frequently are available such as ± repositioning, ± splinting and ± antibiotics . For treatment of crown fractures with exposed dentin and/or the pulp the amount of research needed before reliable answers to all treatment possibilities have been covered seems formidable. For crown-root fractures there are several treatment options and extensive research is needed before reliable answers can be established as to which treatment option offers the best possible treatment.

The multitude of possible trauma scenarios and the broad variety of treatment options make it very difficult for lay people and practitioners to provide evidence-based treatment and recommend the best possible treatment choice for the patient. Keeping this in mind, it is not surprising that much dental trauma treatment worldwide is far from ideal. Surveys in many countries worldwide such as England, Australia, New Zealand, Tanzania, Brazil, Switzerland, Sweden, Turkey, Kuwait, Malaysia, Turkey India, Japan, China, Nigeria and Chile have shown that knowledge of adequate treatment of traumatized teeth is deficient, implying that up to half of all treatments offered are either not necessary or directly harmful to the patient.

The Dental Trauma Guide is an attempt to elevate this unfortunate situation by making the current knowledge in dental traumatology easily available on the internet. For 40 years, patient records have been collected at the University Hospital in Copenhagen, creating the information contained in the extensive database used in developing the Dental Trauma Guide for treatment selection and prognosis estimation. Since 1965 standardized documentation of long-term effects of trauma treatments have been collected and this material (4000 cases) together with the results of 80 clinical studies and 65 experimental animal studies using monkeys now forms the scientific basis for the Dental Trauma Guide.

An effort has been made to make the information available in a structured and user friendly fashion allowing the practitioner to develop a correct diagnosis, a treatment plan, and a follow-up plan along with identifying a risk estimate for healing complications.

Arriving at the correct diagnosis

As previously mentioned, a traumatized tooth may suffer one of 96 distinct trauma conditions. The correct choice of treatment is obviously dependent on the ability of the practitioner to make the correct diagnosis. In this respect the Dental Trauma Guide will follow the international WHO classification. To help the newcomers in dental traumatology a Trauma Pathfinder will be incorporated in the website to guide the practitioner via a series of ‘yes’ and ‘no’ questions to a correct diagnosis.

It is very important to register the injuries in a standardized way. The classification by Andreasen is recommended because it is closely related to the treatment. The dental trauma guide will enable the clinician to find all information to be able to diagnose and classify TDI.

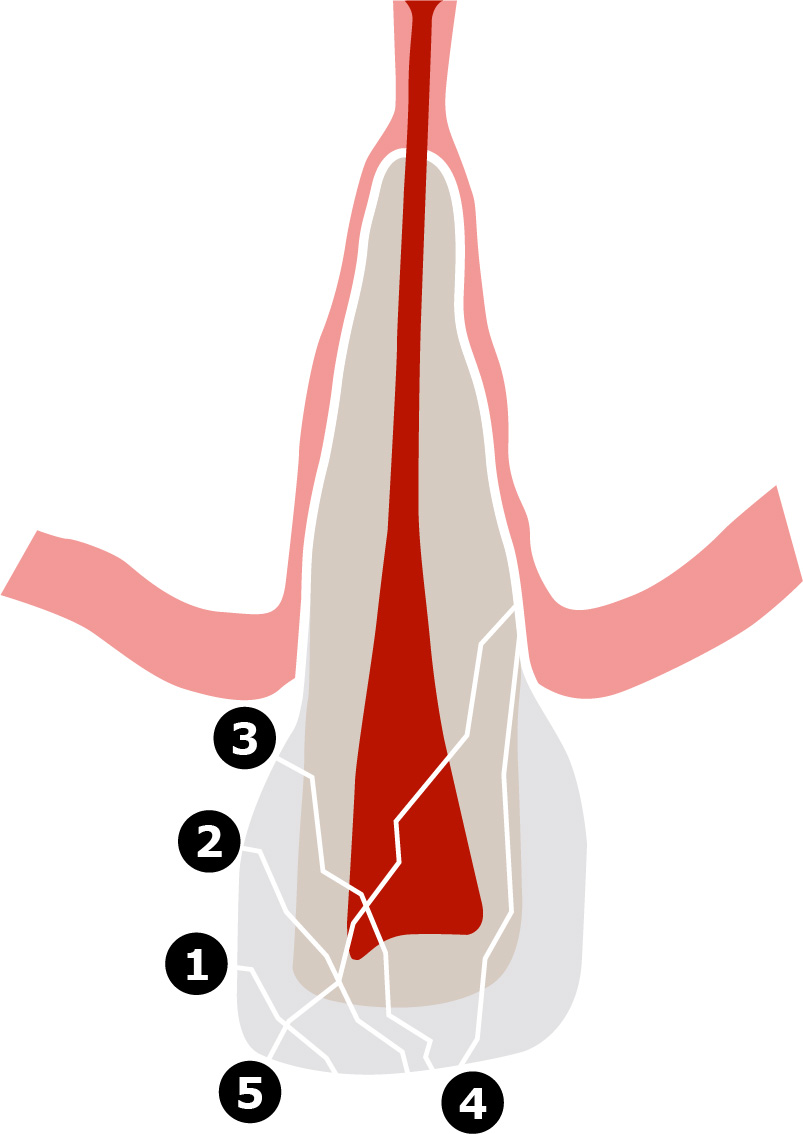

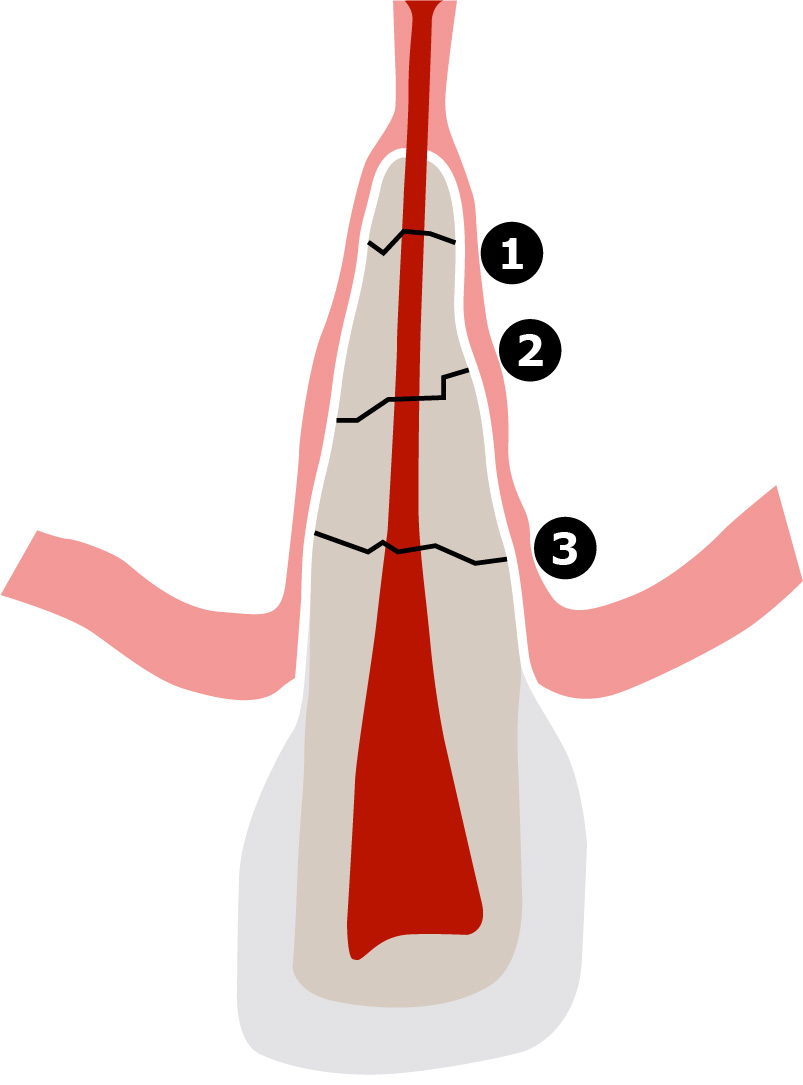

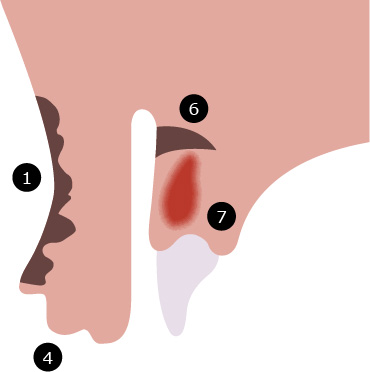

The Eden-Baysal index is a new 5-digit index that will comprise all important information and can be easily computerized. Using this together with a schematic picture illustrating the injuries will simplify for clinicians worldwide, even clinicians with little experience in trauma, to accurately register TDI in the emergency situation. This index enables combination injuries to be registered at the same time (Eden Baysal index). Standardized registration will enable comparison of data and outcome between different centers worldwide enabling larger materials.

Eden Baysal index

Examples of use of the index:

Left central incisor with extrusive luxation can be described with the 5-digit code: (21)00Ei-

Right lateral incisor with crown root fracture with pulp exposure and immature root development: (12)50Ni-

Left central incisor with crown facture with pulp exposure and lateral luxation with alveolar process fracture will get the code: (21)30Lm+

Lateral incisor with crown fracture in dentin without pulp exposure and root fracture in apical third of the root with mature apex (12)21Nm-

Selecting treatments which may optimize pulp and periodontal healing

A paradox in dental traumatology is that almost all treatment procedures impose an element of new trauma when applied, i.e. being traumatogenic. To mention a few, repositioning of a displaced tooth manually or by forceps will damage or destroy thousands or millions of PDL cells. Application of many types of splints, especially arch bars, in which loosened teeth are fastened to an arch bar with wires will create large compression zones in the PDL due to tightening of the steel wires and establish invasion paths for bacteria along subgingivally placed wires. Insufficient coverage of exposed dentin and pulp may lead to microleakage with formation of anaerobic bacterial colonies, which may seriously damage the pulp. Proper treatment selection, which sometimes means minimal or no treatment, is therefore crucial.

In the Dental Trauma Guide, treatment approaches are presented according to the present guidelines from the International Association of Dental Traumatology. These guidelines are developed by international specialists in Dental Traumatology based on available evidence and best clinical practice.

Follow-up regimens for dental trauma patients

An optimal follow-up plan should aim at selecting points in time where the chances of diagnosing healing complications are most effective. For obvious reasons, cost and the convenience of the patient and practitioner have to be taken into consideration when construction a good and cost-effective control system. The suggested follow-up plan for a given trauma entity is based on a series of clinical studies where survival analysis has documented the most optimal time for diagnosis of pulp and periodontal healing complications.

Description and diagnosis of healing complications.

In the Dental Trauma Guide the terminology of healing complications has been based on the 2020 edition of the Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Dental Injuries by Andreasen et al. In relation to pulpal healing the following outcome descriptions are used:

- Pulp necrosis (sterile or infected)

- Pulp canal obliteration (partial or total)

In relation to PDL healing the following healing complications are described:

- External repair-related resorption (External surface resorption)

- External ankylosis-related resorption (osseous replacement resorption)

- External infection related resorption (Inflammatory resorption)

Concerning the marginal periodontium the following healing complication is described:

- Traumatic loss of marginal bone

Finally, and probably the most essential complication is tooth loss usually caused by the abovementioned healing complications.

Prediction of healing complications

Several clinical studies have been done to identify healing/non healing predictors for the various trauma entities. These studies have so far identified 15 predictors, which have been significantly linked to the occurrence of healing complications. Some of these factors have been shown to be very strong (type and extent of injury and stage of root development) whereas others only have a minor influence (treatment). The identification of these factors is usually based on a multivariate statistical analysis with regression analysis being the primary tool. To some extent the influence these predictors has on pulp and periodontal healing can be verified by the result found from the monkey experiments.

One of the goals for the Dental Trauma Guide is to give the dental practitioner a tool whereby a risk profile based on the most important predictors can be developed for an individual patient with a given trauma entity.

Presently the trauma archives at the University Hospital contains 40.000 patient trauma records, all having standardized clinical, radiographic and photographic documentation of the type and extent of the injury including associated soft tissue injuries as well as information about the treatment offered. Approximately 10 %, or 4000 patients, have had long-term follow-up of 1-10 years and these patients constitute the core of the trauma database. These traumas are to a large extent representative for the 96 different trauma scenarios (see earlier). The database is constantly expanded by new trauma cases evaluated in the Dental Trauma Guide trauma clinic.

Recommended reading

1. ANDREASEN JO, LAURIDSEN E, DAUGAARD-JENSEN J. Dental traumatology: an orphan in pediatric dentistry? Pediatric Dentistry 2009; 31: 133-36.

2. RICHARDS D, LAWRENCE A. Evidence based dentistry. Brit Dent J 1995: 270 – 273.

3. BADER J, ISMAIL A. Survey of systematic reviews in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135: 464.

4. TORABINEJAD M, BAHJRI K. Essential elements of evidenced-based endodontics: steps involved in conducting clinical research. J Endod 2005; 31: 563 – 569.

5. ANDREASEN JO; ANDERSSON L. Critical considerations when planning experimental in vivo studies in dental traumatology. Dent Traumatol 2011; 27: 275-280

6. ANDREASEN JO. Review article. Experimental dental traumatology. Development of a model for external root resorption. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987; 3:269-287.

7. ANDREASEN JO. History behind the Dental Trauma Guide. Dent Traumatol 2009; 25. In preparation.

8. ANDREASEN JO, SKOUGAARD MR. Reversibility of surgically induced dental ankylosis in rats. Int J Oral Surg 1972; 1:98-102

9. ANDREASEN JO, ANDREASEN FM, MEJÀRE I, CVEK M. Healing of 400 intra-alveolar root fractures. 2. Effect of treatment factors such as treatment delay, repositioning, splinting type and period of antibiotics. Dent Traumatol 2004; 20:203-211.

10. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO. Important considerations for designing and reporting epidemiologic and clinical studies in dental traumatology. Dent Traumatol 2011; 27: 269-274

11. ANDREASEN JO, JENSEN SS, SAE-LIM V. The role of antibiotics in preventing healing complications after traumatic dental injuries: A literature review. Endod Topic 2006, 14, 80-92.

12. ANDREASEN ET AL. Development of an interactive Dental Trauma Guide. Pediatric Dentistry 2009; 31,133-6.

13. ANDREASEN JO, VINDING TR, AHRENSBURG SS. Etiology and predictors for healing complications in the permanent dentition after dental trauma. A review. Endod Topics 2006;14: 20-27.

14. ANDREASEN FM, ANDREASEN JO, LAURIDSEN E. Luxation Injuries of Permanent Teeth: General Findings. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2018. pp. 413-442

15. ANDREASEN FM, LAURIDSEN E, ANDREASEN JO. Crown Fractures. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2018. pp.327-354.

16. ANDREASEN JO, ANDREASEN FM, TSUKIBOSHI, EICHELSBACHER F. Crown-Root Fractures. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2018. pp. 355-376

17. STOKES AN, ANDERSON HK, COWAN TM. Lay and professional knowledge of methods for emergency management of avulsed teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol 1992; 8: 160-162.

18. HAMILTON FA, HILL FJ, HOLLOWAY PJ. An investigation of dento-alveolar trauma and its treatment in an adolescent population. Part 1: the prevalence and incidence of injuries and the extent and adequacy of treatment received. Brit Dent 1997; 182: 91-95.

19. HAMILTON FA, HILL FJ, HOLLOWAY PJ. An investigation of dento-alveolar trauma and its treatment in an adolescent population. Part 2: dentists’ knowledge of management methods and their perception of barriers to providing care. Brit Dent 1997; 182: 129-133.

20. KAHABUKA FK, WILLEMSEN W, van HOF M, NTABAYE MK, BURGERSDIJK R, FRANKENMOLEN F, PLASSCHAERT A. A initial treatment of traumatic dental injuries by dental practitioners. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998; 14: 206-209.

21. MAGUIRE A, MURRAY JJ, AL-MAJED I. A retrospective study of treatment provided in the primary and secondary care services for children attending a dental hospital following complicated crown fracture in the permanent dentition. Internat Paediatric Dent 2000; 10: 182-190.

22. STEWART SM, MACKIE IC. Establishment and evaluation of a trauma clinic based in a primary care setting. Int. J Paediatr Dent 2004; 14: 409-416.

23. KOSTOPOULOU MN, DUGGAL MS. A study into dentists’ knowledge of treatment of traumatic injuries to young permanent incisors. Int. J Paediatr Dent 2005; 15: 10-19.

24. JACKSON NG, WATERHOUSE PJ, MAGUIRE A. Factors affecting treatment outcomes following complicated crown fractures managed in primary and secondary care. Dental Traumatol 2006; 22: 179-185.

25. HU LW, PRISCO CRD, BOMBANA AC. Knowledge of Brazilian general dentists and endodontists about the emergency management of dento-alveolar trauma. Dental Traumatol 2006; 22: 113-117.

26. COHENCA N, FORREST JL, ROTSTEIN I. Knowledge of oral health professionals of treatment of avulsed teeth. Dental Traumatol 2006; 22: 396-301.

27. DE FRANCA RÌ, TRAEBERT J, de LACERDA JT. Brazilian dentists’ knowledge regarding immediate treatment of traumatic dental injuries. Dental Traumatol 2007; 23: 287-290.

28. YENG T, PARASHOS P. An investigation into dentists’ management methods of dental trauma to maxillary permanent incisors in Victoria, Australia. Dental Traumatol 2008; 24: 443-448.

29. KRASTI G, FILIPPI A, WEIGER R. German general dentists’ knowledge of dental trauma. Dental Traumatol 2009; 25: 88-91.

30. ANDERSSON L, PETTI S, DAY P, KENNY K, GLENDOR U, , ANDREASEN JO. Classification, Epidemiology and Etiology. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2019. pp.252-294.

31. ANDREASEN JO, LØVSHALL H. Response of Oral Tissues to Trauma. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2019. pp.66-131.

32. ANDERSEN PK, ANDREASEN FM, ANDREASEN JO. Prognosis of Traumatic Dental Injuries. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2019. pp. 955-961.

33. ANDREASEN FM, ANDREASEN JO, TSUKIBOSHI M, COHENCA N. Examination and Diagnosis of Dental Injuries. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2019. pp. 295-326.

34. GLENDOR U, ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO. Economic Aspects of Traumatic Dental Injuries. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, (eds.). Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth (5th ed.). Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell 2019. pp.982-991.

35. EDEN E, BAYSAL M, ANDERSSON L. Eden Baysal Dental Trauma Index: Face and content validation. Dent Traumatol. 2020 ;36:117-123.

36. ANDERSSON L, FRISKOPP J, BLOMLÖF L. Fiber-glass splinting of traumatized teeth. J Dent Child 1983; 50:21-24.

37. BLOMLÖF L, ANDERSSON L, LINDSKOG S, HEDSTRÖM K-G, HAMMARSTRÖM L. Periodontal healing of replanted monkey teeth prevented from drying. Acta Odontol Scand 1983; 41:117-123.

38. BLOMLÖF L, LINDSKOG S, ANDERSSON L, HEDSTRÖM K-G, HAMMARSTRÖM L. Storage of experimentally avulsed teeth in milk prior to replantation. J Dent Res 1983; 62:912-916.

39. ANDERSSON L, BLOMLÖF L, LINDSKOG S, FEIGLIN B, HAMMARSTRÖM L. Tooth ankylosis. Clinical, radiographic and histological assessments. Int J Oral Surg 1984; 13:423-431.

40. ANDERSSON L, LINDSKOG S, BLOMLÖF L, HEDSTRÖM K-G, HAMMARSTRÖM L. Effect of masticatory stimulation on dentoalveolar ankylosis after experimental tooth replantation. Endod Dent Traumatol 1985;1:13-16.

41. HAMMARSTRÖM L, BLOMLÖF L, FEIGLIN B, ANDERSSON L, LINDSKOG S. Replantation of teeth and antibiotic treatment. Endod Dent Traumatol 1986;2:51-57.

42. ANDERSSON L, JONSSON BG, HAMMARSTRÖM L, BLOMLÖF L, ANDREASEN JO, LINDSKOG S. Evaluation of statistics and desirable experimental design of a histomorphometrical method for studies of root resorption. Endod Dent Traumatol 1987:3:288-95.

43. ANDERSSON L. Dentoalveolar ankylosis and associated root resorption in replanted teeth. Experimental and clinical studies in monkeys and man. Swedish Dental Journal Suppl 1988: 56: 1-75

44. ANDERSSON L, BODIN I, SÖRENSEN S. Progression of root resorption following replantation of human teeth after extended extra-oral storage. Endod Dent Traumatol 1989;5:38-47.

45. ANDERSSON L, BODIN I. Avulsed human teeth replanted within 15 minutes – a long-term clinical follow-up study. Endod Dent Traumatol 1990;6:37-42

46. ANDERSSON L. Progression of replacement resorption after replantation of avulsed teeth. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Dental Trauma. Folksam, Stockholm, 1991

47. GLENDOR U, HALLING A, ANDERSSON L, EILERT-PETERSON E. Incidence of traumatic tooth injuries in children and adolescents in the county of Västmanland, Sweden. Swed Dent J 1996:20;15-28

48. PETERSSON EE, ANDERSSON L, SÖRENSEN S. Traumatic oral vs non-oral injuries. An epidemilogical study during one year in a Swedish county. Swed Dent J 1997:21:55-68

49. GLENDOR U, HALLING A, ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN J O, KLITZ I. Type of treatment and estimation of time spent on dental trauma. – A longitudinal and retrospective study. Swed Dent J 1998;22:47-60.

50. ANDERSSON L, MALMGEN B. The problem of Dentoalveolar ankylosis and subsequent replacement resorption in the growing patient. Australian Endodontic Journal 1999; 25:57-61

51. GLENDOR U, HALLING A, BODIN L, ANDERSSON L, NYGREN Å, KARLSSON G, KOUCHECKI B. Direct and indirect time spent on care of dental trauma: a 2 year prospective study of children and adolescents. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2000;16:16-23.

52. GLENDOR U, SVENSSON L-I, ANDERSSON L. Tand och käkskador vid idrott. En Folksam studie om 5000 forsäkringsanmälda tand- och käkskador under åren 1994-1997. Folksam, Stockholm 2002.

53. ANDERSSON L, EMAMI-KRISTIANSEN Z, HOGSTROM J. Single-tooth implant treatment in the anterior region of the maxilla for treatment of tooth loss after trauma: A retrospective clinical and interview study. Dental Traumatology 2003;19:126-131

54. ANDERSSON L, AL-ASFOUR A, AL-JAME Q. Knowledge of first aid measures of avulsion and replantation of teeth. An interview study of 221 Kuwaiti schoolchildren. Dent Traumatol 2006; 22: 57-65.

55. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO. Soft tissue injuries. (Chapter author) Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the teeth, 4th edn, Oxford: BlackwellMunksgaard; 2007.

56. TSUKIBOSHI M, ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO. Transplantation of teeth (Chapter author) Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the teeth, 4th edn, Oxford: BlackwellMunksgaard 2007

57. GLENDOR U, ANDERSSON L. Resources spent on Dental Injuries. (Chapter author) Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the teeth, 4th edn, Oxford: BlackwellMunksgaard 2007

58. AL-JAME Q , ANDERSSON L, A AL-ASFOUR. Kuwaiti parents’ knowledge of first aid measures of avulsion and replantation of teeth, an-interview study in Kuwait. Medical Princ Pract 2007; 16: 274-279.

59. ABU-DAWOUD M, AL-ENEZI B, ANDERSSON L. Knowledge of emergency management of avulsed teeth among young physicians and dentists. Dent Traumatol 2007;23: 348-355

60. AL ASFOUR A, ANDERSSON L, AL-JAME Q. School teachers’ knowledge of tooth avulsion and dental first aid before and after receiving information about avulsed teeth and replantation. Dent Traumatol. 2008:24: 43-49

61. AL ASFOUR A, ANDERSSON L The effect of a leaflet given to parents for first aid measures after tooth avulsion. Dent Traumatol 2008; 24:515-521

62. HASAN AA, QUDEIMAT MA, ANDERSSON L. Dent Traumatol. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries in preschool children in Kuwait – a screening study.2010;26:346-50.

63. ANDERSSON L, TSUKIBOSHI M, ANDREASEN JO. Tooth transplantation. Chapter 17 in textbook Andersson L, Kahnberg K-E, Pogrel MA (Editors) Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. Wiley, Oxford. 2010.

64. ANDERSSON L. Availability of emergency dental treatment – a question of organization. Editorial. Dent Traumatol 2010; 26:211

65. ANDERSSON L. Emerging countries in dental trauma research. Editorial. Dent Traumatol 2010;26: 303

66. ANDREASEN JO, ANDREASEN FM, BAKLAND LK, FLORES MT, ANDERSSON L. Traumatic Dental Injuries. A Manual, 3rd edn. Oxford: Wiley, 2011.

67. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO. Important consideration for designing and reporting epidemiologic and clinical studies in dental traumatology. Dent Traumatol 2011; 27:269-274.

68. ANDREASEN JO, ANDERSSON L. Critical considerations when planning experimental in vivo studies in dental traumatology in vivo. Dent Traumatol 2011; 27:275-280.

69. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO, KRISTENSEN KF. Writing an original article for publication in Dental Traumatology. Dent Traumatol 2011;24: 328-333

70. AL SANE M, BOURISLY N, ALMULLA T, ANDERSSON L. Lay peoples’ preferred sources of health information on the emergency management of tooth avulsion. Dent Traumatol. 2011; 27:432-437.

71. DIANGELIS AJ, ANDREASEN JO, EBELESEDER K, KENNY DJ, TROPE M, SIGURDSSON S, ANDERSSON L ET AL. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2012; 28:2-12

72. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO, DAY PF, HEITHERSAY G, TROPE M, DIANGELIS AJ, KENNY DJ ET AL International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth Dent Traumatol 2012;28: 88-96

73. ANDERSSON L. New Guidelines for treatment of avulsed permanent teeth. Editorial. Dent Traumatol 2012; 28:87

74. MALMGREN B, ANDREASEN JO, FLORES MT, ROBERTSON A, DIANGELIS AJ, ANDERSSON L, CAVALLERI G ET AL. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 3. Injuries in the primary dentition. Dent Traumatol. 2012; 28:174-82.

75. ANDERSSON L. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries. J Endod. 2013 Mar;39(3 Suppl): S2-5

76. ANDERSSON L. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries. Pediatr Dent. 2013; 35:102-5.

77. ANDERSSON L. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries. J Endod. 2013;39: (3 Suppl):2-5.

78. ALNAGGAR D, ANDERSSON L. Emergency management of traumatic dental injuries in 42 countries. Dent Traumatol. 2015; 31: 89–96

79. ANDERSSON L. Our duty to promote local emergency services for traumatic dental injuries. Contem Clin Dent 2015;6: S1-2.

80. JAFARZADEH H, SARRAF SHIRAZI A, ANDERSSON L. The most-cited articles in dental, oral, and maxillofacial traumatology during 64 years. Dent Traumatol. 2015; 31:350-60.

81. BEN HASSAN MW, ANDERSSON L, LUCAS PW. Stiffness characteristics of splints for fixation of traumatized teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2016; 32:140-5

82. DIANGELIS AJ, ANDREASEN JO, EBELESEDER KA, KENNY DJ, TROPE M, SIGURDSSON A, ANDERSSON L, BOURGUIGNON C, FLORES MT, HICKS ML, LENZI AR, MALMGREN B, MOULE AJ, POHL Y, TSUKIBOSHI M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 1. Fractures and Luxations of Permanent Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2016; 38:358-368.

83. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO, DAY P, HEITHERSAY G, TROPE M, DIANGELIS AJ, KENNY DJ, SIGURDSSON A, BOURGUIGNON C, FLORES MT, HICKS ML, LENZI AR, MALMGREN B, MOULE AJ, TSUKIBOSHI M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 2. Avulsion of Permanent Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2016; 38:369-376.

84. MALMGREN B, ANDREASEN JO, FLORES MT, ROBERTSON A, DIANGELIS AJ, ANDERSSON L, CAVALLERI G, COHENCA N, DAY P, HICKS ML, MALMGREN O, MOULE AJ, ONETTO J, TSUKIBOSHI M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 3. Injuries in the Primary Dentition. Pediatr Dent. 2016; 38:377-385.

85. MALMGREN B, ANDREASEN JO, FLORES MT, ROBERTSON A, DIANGELIS AJ, ANDERSSON L, CAVALLERI G, COHENCA N, DAY P, HICKS ML, MALMGREN O, MOULE AJ, ONETTO J, TSUKIBOSHI M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 3. Injuries in the Primary Dentition. Pediatr Dent. 2017; 39:420-428.

86. DIANGELIS AJ, ANDREASEN JO, EBELESEDER KA, KENNY DJ, TROPE M, SIGURDSSON A, ANDERSSON L, BOURGUIGNON C, FLORES MT, HICKS ML, LENZI AR, MALMGREN B, MOULE AJ, POHL Y, TSUKIBOSHI M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 1. Fractures and Luxations of Permanent Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2017; 39:401-411.

87. ANDERSSON L, ANDREASEN JO, DAY P, HEITHERSAY G, TROPE M, DIANGELIS AJ, KENNY DJ, SIGURDSSON A, BOURGUIGNON C, FLORES MT, HICKS ML, LENZI AR, MALMGREN B, MOULE AJ, TSUKIBOSHI M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 2. Avulsion of Permanent Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2017; 39:412-419.

88. AL-MUSAWI A, AL-SANE M, ANDERSSON L. Smartphone App as an aid in the emergency management of avulsed teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2017; 33:13-18

89. MASLAMANI M, ALMUSAWI A, JOSEPH B, GABATO S, ANDERSSON L. An experimental model for studies on delayed tooth replantation and ankylosis in rabbits. Dent Traumatol. 2016; 32:443-449.

90. KENNY KP, DAY PF, SHARIF MO, PARASHOS P, LAURIDSEN E, FELDENS CA, COHENCA N,SKAPETIS T, LEVIN L, KENNY DJ, DJEMAL S, MALMGREN O, CHEN YJ, TSUKISBOSHI M,ANDERSSON L. What are the important outcomes in traumatic dental injuries? Aninternational approach to the development of a core outcome set. Dent Traumatol. 2018; 34:4-11.

91. MASLAMANI M, JOSEPH B, GABATO S, ANDERSSON L. Effect of periodontal ligament removal with gauze prior to delayed replantation in rabbit incisors on rate of replacement resorption. Dent Traumatol. 2018; 34:182-187

92. PETTI S, GLENDOR U, ANDERSSON L. World traumatic dental injury prevalence and incidence, a meta-analysis-One billion living people have had traumatic dental injuries. Dent Traumatol. 2018; 34:71-86.

93. PETTI S, ANDREASEN JO, GLENDOR U, ANDERSSON L. The fifth most prevalent disease is being neglected by public health organisations. Lancet Glob Health. 2018; 6:e1070-e1071.

94. LAURIDSEN E, ANDREASEN JO, BOUAZIZ O, ANDERSSON L. Risk of ankylosis of 400 avulsed and replanted human teeth in relation to length of dry storage: A re-evaluation of a long-term clinical study. Dent Traumatol. 2019 Oct 20. doi: 10.1111/edt.12520. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 31631495.